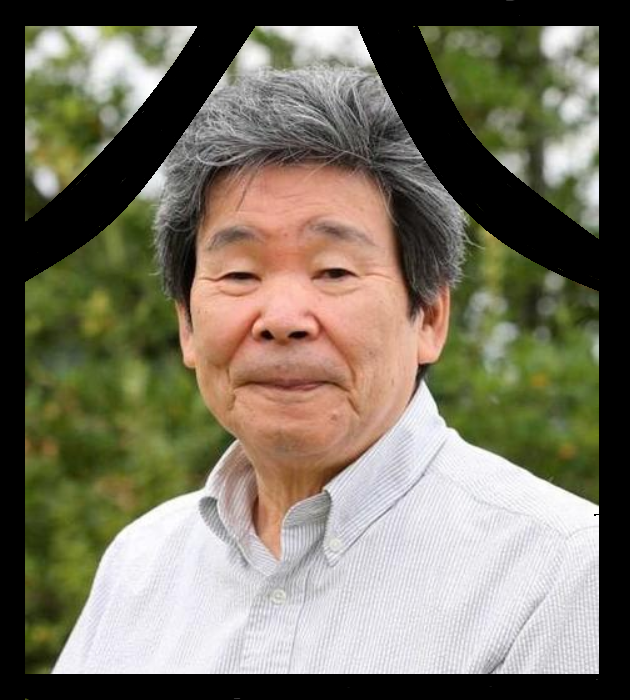

REMEMBERING ISAO TAKAHATA

Image source: Daily Sports Online

On April 5, Isao Takahata died. His is not a name familiar to most people. Even though he made films at the renowned Studio Ghibli, which has done more than any other studio to make anime (Japanese animation) respected and admired worldwide, he sort of flew under the radar. Hayao Miyazaki is more associated with Ghibli, and might even eclipse it in fame. This is fair given the quantity and quality of his filmography, but Takahata always seemed to get less credit than he deserved. Without Miyazaki, he would be considered a giant of the industry.

Takahata’s career stretches all the way back to the early days of the anime industry, or at least the period when it was reconstructing itself from the shakeup of World War II. He got his start at Toei, Japan’s biggest studio and the creator of movies like Legend of the White Serpent and Journey to the West that provided Eastern rivals to Disney’s fairy tale stories. His first film, Horus: Prince of the Sun (1968), was groundbreaking for its time, with excellent animation, violent action sequences, and political subtext to lure in an older crowd. But it flopped financially, and Takahata went on to work in TV for the next decade. That being said, the shows he worked on then — Heidi, Girl of the Alps, 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother, and Anne of Green Gables — were very influential and beloved by both Japanese and European viewers of all ages.

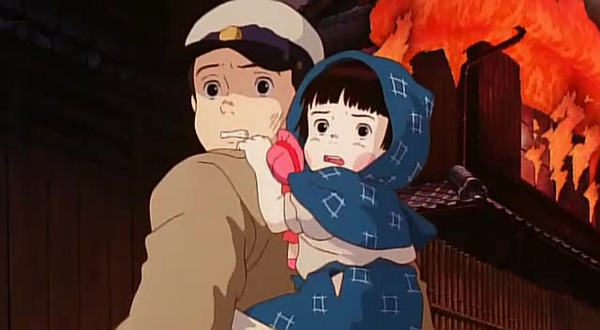

Image source: Naze-no Chibenkaku

But ultimately, what Takahata will be remembered for most is Grave of the Fireflies (1988). This is one of those movies that’s on the short list of most Anime You Need to See Before You Die lists (even if it didn’t actually make it onto my own…). Based on the memoir of a World War II survivor, it recounts the struggles of two kids, a little girl and her teenage brother, to get by in the devastation of the war. It pulls no punches. While it is part of an unfortunate narrative Japan has embraced that portrays itself as a pitiful victim of a war it had started through its own imperialist aggression — indeed, it’s become one of that narrative’s central texts — it’s an incredibly powerful story, and a great way of getting a sense for what it’s like to live in a war zone, when any given day could be your last. Along with Akira, which also came out in 1988, it exploded the notion that animation is inherently childish and blew several unsuspecting viewers’ minds. While it will always be remembered for its tearjerker ending, it has a more sophisticated emotional range than just melancholy: the movie is really about the boy doing whatever he can to take care of his little sister. His love for her is touching, and he does everything from flips on monkey bars to firefly-catching to keep his sister happy and distracted from her grim reality.

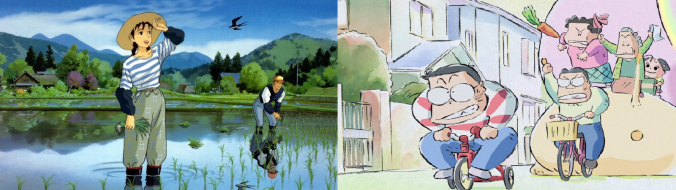

Image sources: So-net Blog and The Rising Sky

This is probably Takahata’s most enduring legacy: his penchant for making movies that draw out the viewers’ emotions and leave them deeply moved. Grave of the Fireflies is most direct in this regard — it makes you depressed — but his other movies usually aim for a more wistful, reflective tone. Only Yesterday (1991) languished in obscurity for decades because it’s not the kind of movie easy to market internationally: it’s about an adult woman reminiscing about her childhood while on a visit to the Japanese countryside to pick safflowers for a while. That means it’s too slow and emotionally complex for kids, yet too culturally and demographically specific for most adults. But it combines heartfelt reflection on the direction of your life with touching, often funny, anecdotes about childhood in Japan in the ’60s. My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999), a series of anecdotes about a mostly ordinary family, is more sitcom-like, but it’s still very sentimental in its portrayal of the Yamadas’ quirks and foibles, and its ending song, “Que Sera, Sera,” is a surprisingly wistful way of closing the movie. (Takahata also directed an obscure movie in 1981, Chie the Brat, which also portrayed domestic life in ’60s Japan comically, but with a darker edge since the family is more low-class.)

Despite Fireflies‘ reputation, I actually think my favorite Takahata work is his last, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013). Takahata never did any animation work himself and had a reputation for workmanlike art in his movies; Kaguya is basically him showing the world what he was capable of before dying. Based on a famous Japanese fairy tale, it looks like an old Japanese scroll come to life, with lines drawn sketchily and coloring evoking watercolors and storybooks. Some of its scenes depict emotional turmoil in a raw, evocative way live-action never could, and watching it is like watching a literal work of art. (This was before Loving Vincent took animated art to the next level.) The story is about a girl mysteriously found inside of a bamboo stalk by an old couple who grows much faster than usual. Despite her happy life in the countryside with her loving parents and kid friends, she is soon sent off to live in the capital and marry into nobility. But she can’t quite feel at home there and can’t shake the feeling that she doesn’t belong on Earth at all. It’s a poignant story, very weird, as most fairy tales are, and while you may be conflicted over how to feel about its resolution, it’s hard not to feel something, given how we’ve followed this girl’s life for so long.

Takahata’s movies were always less marketable than Miyazaki’s. Starving kids in World War II, a grown woman coming to terms with her own childhood, anthropomorphic tanuki (raccoon-like animals) scheming how to save their hill from human development, an idiosyncratic fairy tale with a meandering plot — these aren’t the kind of movies that bring huge crowds, and ever since Horus, Takahata’s films performed underwhelmingly. As a result, he ceded the limelight to Miyazaki, even though he was older and more or less mentored Miyazaki early in their careers. He took long breaks to do things like make live-action documentaries about canals. I’ve never heard someone gush about him or cite him as an inspiration or their favorite anime director. But Takahata’s movies deserve a prominent place in the anime pantheon. They thoughtfully portray life’s challenges, sometimes tragically, sometimes comically, often with great subtlety. They challenge the notion that animation is for action, wacky gags, epic spectacle or speculative fiction (sci-fi/fantasy). They tend to leave you lost in thought or even sobbing at the end. I couldn’t help thinking after seeing Kaguya that this was someone the world had drastically underrated and overlooked, and it was partly his fault: for all its charms, a movie like Kaguya is awfully old-fashioned for the 2010s. But it’s a towering achievement, as is Takahata’s filmography overall. Watching his films is a way to get a sense of a quieter, more mundane side of Japan, but with flights of fancy you don’t get in most live-action movies. With his death and Miyazaki’s decline, the sense that Ghibli has moved on from its glory days only grows more and more acute; and knowledge of how sensitive and moving his work was made his demise that much more painful.