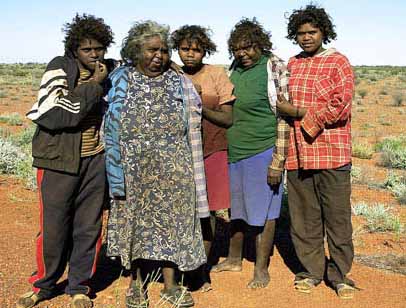

Image source: Crystalinks

Australia prides itself as one of the world’s most multicultural societies. On a foundation of British culture, it’s composed of big Italian, Greek, Indian, Chinese, German, Vietnamese, Filipino, Korean, and South African minorities. Its big cities are a melange of cultures and faces, and immigrants from all over the globe are (mostly) welcomed here. Immigrants continue to flock to Australia, drawn by its enviable living standards, its tolerant atmosphere, and its easygoing attitude. Yet underneath the surface, Australia continues to cope with the problems afflicting its least successful minority: the Aborigines, its first people.

BACKGROUND

People have lived in Australia for at least 40,000 years, and possibly as long as 100,000 years. They most likely moved south from the southeast Asian islands (although there is new evidence that some were descended from the Indus Valley civilization in ancient Pakistan c. 2000 BCE). They adapted to the continent’s brutal climate and environment, surviving by living in simple dwellings, dressing lightly, and hunting and gathering for food. Like foraging peoples elsewhere, they developed an intimate attachment to the land, studying water flow, animal migration patterns, and the rugged topography. They transmitted this knowledge through the generations orally, along with stories of their ancestors and the beings that created the wonders around them, a mythology lumped together by non-Aboriginals as “the Dreamtime.” Rock art in caves around the continent show their preoccupation with nature and the cosmos.

This culture, while rich and unique in its own terms, never developed technology past the Stone Age and never organized into societies beyond small tribal groups. As a result, British voyagers in the 1700s decided it was “unoccupied” (because only farming people count as occupiers, apparently) and decided to start a prison colony there. Over the 1800s, British colonists overran the continent, quickly seizing the fertile east for themselves. Aborigines were steadily pushed inland, then onto the margins of towns, then into the vast deserts in the center. Denied the ability to make a living off the land any more, most drifted into a stupor of homelessness and alcoholism. Others were able to find work in mines or ranches, but in slave-like conditions, and they were forced to live in reservations. Resistance was futile; facing guns, superior numbers, and disciplined organization, massacres and wars awaited Aborigines who tried to fight. Smallpox and malaria wiped out whole tribes. The Tasmanians (who lived on an island south of Australia) almost disappeared entirely in what’s considered history’s most “successful” genocide.

By the 1890s, the state of the Aborigines — marginalized, destitute, and bereft of opportunity — was pathetic enough that the new Australians spoke of them as a “dying race” who must be treated well and cared for in preparation for their ultimate passing. This meant concerted efforts at population control and assimilation into white society. Children born to Aboriginal mothers with white fathers were taken from Aboriginal communities and enrolled in boarding schools that taught them English, Christianity, and Western values while thoroughly eradicating any Aboriginal culture they might have imbibed. In some cases this attempt at enveloping Aborigines into the new, British-influenced Australian society succeeded, with the kids growing into well-educated adults capable of navigating 2 societies and interpreting the cultures for each other. In other cases, the kids never got over the trauma of abduction from their families and tribes, and grew up haunted, melancholy, and troubled — the so-called “Stolen Generations.” The disruption in family life and demolition of cultural traditions this caused has led the policy to be labeled “cultural genocide.”

Needless to say, Aborigines did not die out. They lived on, struggling but managing, and especially in the Northern Territory, the part of the country least colonized by white settlers. In the 1960s, thanks in no small part to the global movement in favor of indigenous rights and in recognition of indigenous peoples’ achievements, Aborigines began to speak out. They gained the right to vote, to own land, to be counted in the national census. The abduction policy was phased out. Whites stopped referring to Aborigines and their culture in racist terms (in official contexts at least).

The following decades saw a growing awareness among Australians of how much they owed to Aborigines, and growing interest in their history and lifestyles. Aborigines used the opportunity to lobby harder for recognition and rights. Lacking representation of their own in Australia’s parliament, they set up an “Aboriginal Embassy” (a tent) on Parliament grounds to publicize how marginalized they were. Australia Day in 1988, the 200th anniversary of the founding of Sydney (and therefore Australia), was regarded as “Invasion Day” by Aborigines and sympathetic outsiders and celebrated with protests. Ranches and mines were forced to pay Aborigines as much as whites. The crowning achievement might have been Mabo v Queensland in 1992, a High Court ruling that found that Aborigines were entitled to their ancestral land, and recognizing that Australia had not, in fact, been unoccupied in 1788.

CURRENT SITUATION

Australia now recognizes that Aborigines are an integral part of its national culture and self-image. Australian place names (Wollongong, Kalgoorlie, Wagga Wagga, Kakadu, Toowomba) owe a lot to Aboriginal influence; Aboriginal tools like the boomerang, woomera (a spear-thrower), dugout canoes, and coolamon (a wooden carrying vessel) are admired; the Dreamtime has served as a wealth of inspiration for fiction writers far from Australia (although their stories often deviate pretty far from the originals); travelers in the Outback try to emulate the Aborigines’ “walkabouts” (long trips taken across the continent following the “Songlines” left by the ancestors through the landscape).

Aboriginal art is also seeing something of a renaissance. In the past Aborigines would draw on rocks or on the ground. These drawings were mostly practical (where to find game, where to find water, how to get around that mountain), and they were erased after they were needed. But whites saw the artistic value of these drawings and encouraged the artists to transfer the drawings onto canvas or tapestries. This has led to the uniquely Australian “dot painting” style, which is well-represented in Aussie art galleries and especially in Alice Springs, a town in the dead center of the continent that’s emerging as a center of Aboriginal culture. Aboriginal music, especially the bizarre, instantly recognizable sounds of the didgeridoo, has a following. Movies like Rabbit-Proof Fence and Samson & Delilah depict the Aboriginal plight. Aborigines are active in politics, literature, and sports.

Minnie Pwerle, Awelye & Bush Melon. Image source: Central Art

Wintjiya Napaltjarri, Untitled. Image source: Utopia Art Sydney

Makinti Napanangka, Hairstring and Rockholes. Image source: Aboriginal Art Gallery

Yet it’s obvious that Aborigines remain a troubled people. They remain restricted to the margins of urban areas and to squalid camps in the Outback. There is minimal mingling with the other ethnic groups of the country on an everyday basis. 17% are unemployed, 3x the number of the rest of the population. Lame education means they are mostly unskilled, so they mostly work in unskilled, low-paid labor. Welfare dependency is endemic. Without much purpose in life, they gravitate toward alcohol, petrol or glue sniffing, drugs, and begging. Unsurprisingly, they make up over 28% of Australia’s prison population, which only compounds their desperation and despair.

With Aborigines mostly synonymous with “poor, alcoholic bums” in the mainstream perception, addressing the issue is a high priority for the Australian government. How to do so, of course, is a fiercely debated topic. Kevin Rudd, Australia’s prime minister from 2007 to 2010, promised to make every effort to provide for them, and started by offering Aborigines a historic apology in 2008 for the Stolen Generations episode. He continued an earlier policy of restoring land to Aborigines, including mines and other businesses exploiting it, although since the vicissitudes of Australian history make it hard for Aborigines to claim “continuous occupation” of the land, only the Northern Territory has large tracts of Aboriginal-owned land (and that mainly in the desert).

The government has mostly handled the Aboriginal problem by throwing up various layers of bureaucracy to investigate the issue. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, the Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination, the National Indigenous Council — all were government bodies set up to research the situation and recommend policy solutions. Results have been mixed, and depend on whom you ask: some claim that the government has gone a long way into empowering Aborigines and giving them more authority and responsibility for their own affairs while others complain that it still has a racist, paternalist outlook.

The most controversial recent initiative was the Intervention, a drastic measure to quarantine whole Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory and ban alcohol and porno in them as a means of cracking down on pervasive domestic violence. Again, reviews have been mixed: some agree that the intervention was necessary, given how desperate the situation was, while others see it as a heavy-handed, paternalistic, discriminatory action (white families suffering from domestic violence weren’t affected). Noel Pearson, an Aboriginal lawyer who’s emerged as the public advocate for Aboriginal issues, believes that blank welfare checks foster a bleak society and advocates directing more money into Aboriginal education, health care, job training, and economic enterprises to help them cope with the 3rd millennium.

Looking ahead, Australia is considering making amendments to its constitution to get rid of an old clause allowing states to strip voting rights on racial grounds and a clause allowing the national government to legislate on behalf of certain races and replace them with a section affirming Aborigines as the original inhabitants and banning racial discrimination. The idea for a referendum on this issue has been around for years now and almost everyone is O.K. with it, but it still hasn’t happened. Some Aboriginal leaders are adamant about the issue, claiming that the old clauses are offensive and holdovers from a more racist era; others are tired of symbolic gestures and want action. Tony Abbott, the prime minister (until today, anyway), spent a week each year working in a tent in the Northern Territory to spend more time with Aborigines and hear them out.

More guided tours of historically Aboriginal areas, more didgeridoo concerts, and the white prime minister pitching a tent in Arnhem Land are helpful gestures and encouraging signs. But until the living standard statistics for Aborigines start converging with the general population and until Australia makes a more concerted effort to grant them autonomy over their affairs, the malaise and despondency of Aboriginal Australia will probably go on as it has for centuries.