Image source: CNN

AN OPINION PIECE

One of the most contentious issues in America right now is Donald Trump’s vision of a wall along the border with Mexico. It is his signature campaign pledge, the one he kicked off his race with and the theme he returned to most often over the long campaign. Accordingly, building a wall is one of, if not the, main reasons Trump’s supporters voted for him. That makes Republicans in Congress adamant about appropriating funding for it. Democrats are equally adamant about opposing it, however, since it stands against what they stand for. Like many political issues over the past decade in America, this has deadlocked Congress and provoked threats of shutting down the government rather than, you know, actually reaching a deal.

Normally, I hate this kind of brinkmanship and all-or-nothing politics, since all it does is energize the base while leaving urgent problems to fester. Ideally both sides should come together and work out some kind of compromise. However, I find it extremely hard to support that in this case, because the wall isn’t just some kind of flawed policy plan that could feasibly be watered down a bit and passed. It is, quite simply, the dumbest public policy idea I’ve ever heard of. To prove it, here are 10 reasons why.

1. Most Americans don’t even want it. It is important to remember any time Trump does something that makes your blood boil that he lost the popular vote. America uses a system called the Electoral College to choose its presidents; the number of its members is proportional to the population of America’s various states, but they usually vote in blocs for whichever candidate won their state. Trump actually only won 46% of the popular vote. This is hardly a convincing mandate for building a wall, but subsequent polls have shown a dearth of popular support as well. This poll found 57% against it; another one found 63% opposed. As for the states and counties along the border — you know, the ones who would be most affected by this —support is even more tepid. Support is strongest in states like Indiana and Alabama, which love Trump but have relatively few immigrants to stymie in the first place. Considering how big a project like building a wall is, drawing support from a minority of Americans — and a disproportionately old minority at that — is hardly a strong mandate.

2. Immigrants would still find a way in. They always do. Latino immigrants are fleeing desperate poverty and criminal violence; some are so pathetic they feel as if they have nothing to lose in attempting to cross. A wall may be harder to climb than a fence, but determined and well-organized immigrants could still do it. The plan for the wall may include a 6-foot-deep underground section, but immigrants could still tunnel 7 feet deep. (Drug smugglers have long managed to sneak their goods across the border this way.) Some immigrants are already making their way to Canada and crossing America’s other border. (Now there’s a border way too long for a wall.) Drug smugglers, in particular, are resourceful, and come up with devious ways to get around border security — everything from catapults, to wedging drugs in car bodies, to just going around the border by sea. If all else fails, they could always just punch a hole through the wall. The fence currently spanning the border incurred 9,287 breaches between 2010 and 2015. What makes you think a wall would be immune to this?

3. There aren’t even that many immigrants coming in. Trump’s rhetoric may be that dirty, dangerous Mexicans are flooding through the flimsy border, but in actuality there has been a sustained decline in Mexican immigration since 2001. A Pew Research Center report found that 870,000 Mexicans emigrated to America from 2009 to 2014 compared to 1.4 million from 2005 to 2010. This is due partly to the depression in America, partly to improved economic conditions in Mexico, partly to a slowing of the Mexican population growth rate, and partly to immigration enforcement in the US. Like much of Trump’s rhetoric, his descriptions are outdated. America does have a huge ethnic Mexican population, though, which might fuel these misperceptions. (It is also true that immigration from chaotic Central America has picked up.)

4. Immigrants have a beneficial effect on society. This is an important point in rational Democratic arguments, so I won’t go into it too much here, but suffice it to say that Americans should probably want immigrants. Desperate Mexicans are vital components of the American economy and fill the vast majority of low-paid agricultural, construction, restaurant, fishing and domestic jobs — the “dirty work” that whites rarely want to do. In America’s border states they are essential parts of local society. Despite Trump’s ranting about “bringing crime,” immigrants are actually more law-abiding than locals, and despite the perception that they are “taking jobs,” they actually help the economy, and therefore create jobs.

Image source: Brookings Institution

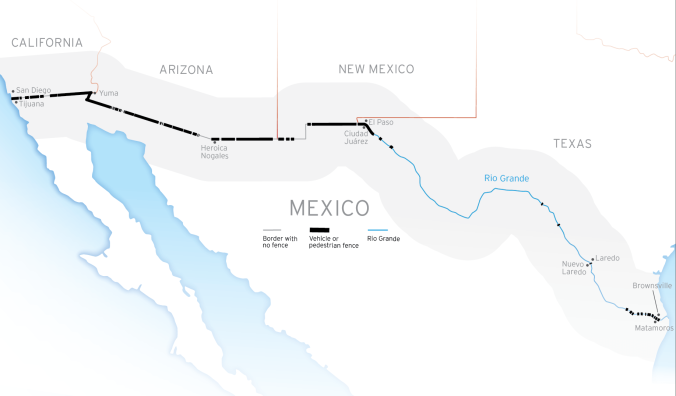

5. Actually building the wall would be a nightmare. Although vast tracts of the US-Mexican border are publicly owned desert, other parts are private property. What if the owners don’t want a wall built on their land? The US government could always negotiate to buy the land, but that would take years. 90 land rights lawsuits over building the border fence are still open from 2008. There are also environmental laws to consider. And what about the Rio Grande, which forms about half of the border? How would the wall work there? What about the mountains that dominate the Arizona-Sonora border? These sorts of logistical issues wouldn’t stymie the building entirely, but it would make it a long-term project that might outlast the lifespans of many Trump voters.

6. There are more innovative ways to secure the border. A wall is a very blunt, old-fashioned solution. For a country as innovative and forward-thinking as America, it’s not a very imaginative solution. Those actually involved in border security would rather opt for things like towers with radar, electro-optical and infrared cameras, aerial monitoring, and ground sensors that rely on AI or machine learning. Given the aforementioned difficulty in keeping out those determined enough to cross perilous distances with little loose money, it would be more practical and cost-effective to focus on detecting illegal border-crossers. Hiring more border security is usually lumped in with the wall in budget debates; it should really just replace the wall entirely.

7. It would ruin Mexican-American relations. Having a wall built on your border is one of the most in-your-face ways to be told “I don’t like you very much.” Trump may claim to be keeping out the “bad hombres,” but in reality he is playing on anti-Mexican sentiment, and Mexico gets it. As a result, Mexican-American relations have free-fallen since the election (really since Trump entered the race in 2015). Only 30% of Mexicans have a favorable opinion of the US, with 42% having a very unfavorable opinion. Anti-American feeling was instrumental in propelling Andrés Manuel Lôpez Obrador, a populist firebrand, to the presidency this year. As a general rule of thumb, it’s not a good idea to be on bad terms with your neighbors. In this specific case, good Mexican-American relations are important because the 2 countries’ economies are very interlinked thanks to NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) and immigration, and because America depends on Mexico for security cooperation. Trump acts like America is wasting money on Mexico, with its security aid, but what would happen if Mexico dropped its intelligence sharing with America? What if Mexico just stopped trying to detain migrants headed north, or looked the other way as drugs are smuggled up there? What if Mexico reneged on its water-sharing agreements and let American farmers wilt?

8. It would be a colossal waste of money. This should be pretty obvious, but walls are expensive. It is estimated that it could cost up to $25 billion. (Democratic estimates reach up to $70 billion, but of course those probably aren’t very accurate.) So much for shrinking the government. This would add to the tax cuts passed last year to further increase America’s budget deficit and basically asks future generations to foot the bill for the older generation’s xenophobia. Trump’s talk of seizing the remittances that Mexican immigrants send or of “making Mexico pay for it” is ridiculous.

9. It would have a chilling effect on immigration and tourism to America. A wall on the Mexican border would mainly affect Mexico and Central America, of course. But it would also send a strong signal that America no longer welcomes immigrants. This is apparent in some Trump voters’ fears that “terrorists” or “ISIS” are sneaking across the border. Even foreigners that reach America by plane would think twice before doing so. Trump’s rhetoric has already lowered the number of tourists, skilled immigrants, and students coming to America. These are important contributors to America’s economy and society. Imagine the harm that could be done if America actually built a wall.

10. It would besmirch what America stands for. As the most powerful argument, I save this for last. Americans get weepy and sentimental about their country being a beacon of hope and freedom. What that basically means is that it serves as a compelling destination for outsiders eager to make something of themselves, to try their luck in America’s dynamic, freewheeling, capitalist economy, and to flee oppression, stagnation and/or danger back home. That is the real symbolism of the Statue of Liberty (“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…”). America is hardly unique in welcoming immigrants from all over the world and moulding them into different people over many generations, but it is the most diverse and influential. Mexicans are not unique in contributing a great deal to American society. There has always been a strand of xenophobia and racism in American society, but by and large most Americans would agree that immigrants are a good thing. If America built a wall, it would no longer be able to claim some sort of moral superiority. It would no longer be able to gloat about bringing down the Soviet empire with its Berlin Wall. It would come to resemble a miserly, suspicious gated community that glares at brown passersby. Given the various impracticalities and stupidities associated with the wall, it should be fairly obvious that it’s meant to be a symbol — but of what? Of an America that sees the outside world as a threat?

So there you have it. The wall is not just dumb, it’s really, really dumb. I haven’t even gone into lesser reasons why it’s stupid, like its possible impact on animal migration patterns or how it would be hard to see what Mexicans might be doing on the other side. It’s so dumb, in fact, that I don’t think it should even be treated as a serious policy idea, but as a crackpot promise tossed out by an attention-hungry mogul looking to energize his political campaign without even considering it seriously. It speaks to how beholden the Republican party has become to deranged fanaticism that so many politicians are willing to treat this as a serious idea. Democrats, and sensible Americans in general, owe it to themselves to stand against such a dumbass idea no matter what.