Tamils can have Scouting events again… but ONLY with armed guards there. Image source: National Geographic

Sri Lanka, a teardrop-shaped island just off the southeastern coast of India, occupies a peculiar place in the global imagination. For the most part, it evokes positive images: lush jungle, frolicking elephants, picturesque hills covered in tea plantations, glorious beaches, peaceful Buddhist temples, and a laid-back lifestyle. And indeed, it’s thrived as an international tourist hotspot, offering visitors a culture similar to India’s without the crowds, hassles and abject poverty that besmirches its neighbor’s reputation.

But there’s another side to Sri Lanka, and it’s almost as well-known: the terrible civil war that gripped the island for 26 years. This was a large-scale, serious conflict with heavy weaponry and lots of civilian casualties. Although tourism has certainly picked up since the end of the war in 2009, Sri Lanka remained a tourist destination for most of the war, and dire reports of terrorist attacks and fierce battles didn’t do much to dent its image.

The war may be over now, but it’s left a lasting legacy of ethnic estrangement and damage. This blog post will delve into how the war started, how it ended, and where the ethnic politics of Sri Lanka stands now.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

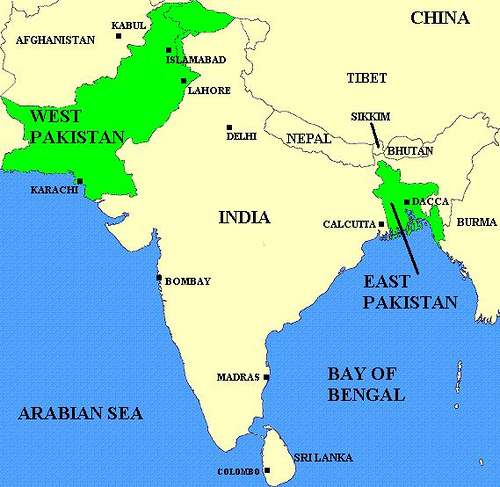

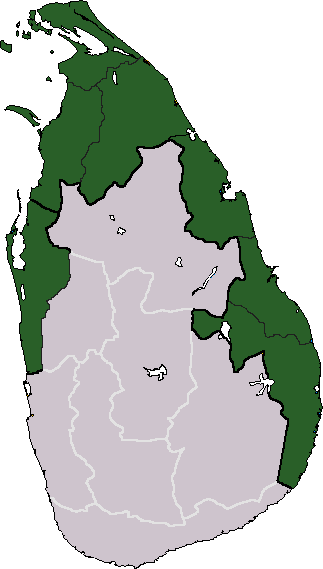

Like oh so many wars in the postcolonial world, Sri Lanka’s civil war was an ethnic conflict. Most of Sri Lanka’s people — 75% — are Sinhalas, a Buddhist ethnicity unique to the island. The rest are almost all Tamils, an ethnic group based in the far south of India — unsurprisingly, the part that’s next to Sri Lanka. They are based in the north and along the east coast.

Sri Lanka has an ancient history, but modern conflict has shrouded its nature in some degree of mystery. Both Sinhalas and Tamils originally came from somewhere else: the Tamils, obviously, from neighboring Tamil Nadu, but the Sinhalas from somewhere in north India — they are racially Aryan like the people of north India. Buddhism thrived in India in ancient times (especially under the Maurya dynasty of the 200s BCE), but diminished in popularity during the Middle Ages, so the Sinhalas’ fervent Buddhism points to a migration sometime before then. Whether the Sinhalas were there first, or whether they were mainly responsible for the impressive civilization whose monuments dominate the island’s central plain, is a contentious debate. Suffice it to say that for most of Lanka’s* history, the two ethnic groups coexisted.

Sri Lanka has a strategic location next to India and along the trade route that spans the Indian Ocean, connecting Arabia and Persia in the west with the Malay archipelago (modern Malaysia and Indonesia) in the east. This meant that various foreigners stopped by throughout its history, including possibly Greeks and Romans. Arabs introduced Islam and converted many Tamils, but most of the population stayed Buddhist or Hindu. In modern times, the Portuguese, Dutch and British each conquered part or all of the island (which they called “Ceylon”), with the latter making the deepest, most permanent inroads, seduced by its ideal climate for growing their all-important tea. Ceylon became a colony where Britishers could get a taste of India without having to deal with its complicated religious conflicts, huge population and political unrest.

That’s not to say that Ceylon didn’t have these things, of course. Like their counterparts in India, British colonists in Ceylon sponsored a minority group in the civil service — in this case, the Tamils — to create a loyal cadre of locals to help stymie native opposition to their rule. Thousands of Tamils were also brought in from India to help pick the tea too, creating a pocket of Tamils in the south (today called “Indian Tamils”). Tamils were better-educated and more likely to speak English than the Sinhalas, further creating the sense of a gulf between them and a connection with their masters.

As a result, when a Ceylonese nationalist movement did emerge in the 1920s, it was mostly Sinhala-led. Sinhalas formed the first government of an independent Ceylon in 1948. In 1956, faced with Sinhalas disgruntled that 2/3 of the civil service was represented by Tamils, the prime minister, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, introduced a “Sinhalese-only” policy: Sinhalese, and only Sinhalese, was to be Ceylon’s official language. Tamils, who rarely speak Sinhalese, protested, and Bandaranaike tried to conciliate them at first, but when Ceylon’s revered Buddhist monks protested in force in favor of the law, Bandaranaike backed down, which incited riots.

The situation continued to deteriorate into the ’60s and ’70s. Politicians found that discriminatory policies played well with Sinhalas, and since they make up such a big proportion of the country their votes were enough to carry elections. So curbs on civil rights continued. Tamils found themselves passed over for university admissions. The army became Sinhala-dominated. Indian Tamils were denied citizenship and encouraged to head back to India. Links with India — student exchanges, media, trade — were severed on socialist grounds, which hurt Tamils disproportionately due to their cross-strait links. Tamils were marginalized economically. The government encouraged Sinhala migration to Tamil areas.

This all contributed to a tense and edgy atmosphere. Parties were split along ethnic lines, and the main issue for Tamil ones was how to cope with the discrimination. Some wanted to work within the system, others argued for a federal system to protect Tamil autonomy, and by the late ’70s an independence movement had emerged. The burning of a library in Jaffna, the largest Tamil city, in 1981 was provocative, but what really pushed Sri Lanka (which had been renamed in 1972) over the edge was a riot in Colombo, its biggest city, in 1983. Provoked by the massacre of a military patrol, Sinhalas took out their anger on ordinary Tamils all over the city by beating, burning, raping and murdering them. The government turned a blind eye to it and never punished anyone for it. To Tamils, the message was clear — they were not welcome in the country any longer.

Some Tamils reacted by emigrating, but the immediate result was civil war. The group that had carried out the ambush in the first place muscled rival parties out of the political arena, sometimes bloodily. The Tamil regions of Sri Lanka were reorganized as an independent country, Tamil Eelam. It had its own flag, government, courts, bank, radio and TV stations, and most of all, military. This military dominated the ersatz country and shaped its life for the next few decades, and although it was called the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, the world knew of them as the “Tamil Tigers.”

The Tamil Tigers’ flag made it clear they weren’t anyone to f*** with.

The Tamil Tigers were hardcore. Led by an intense guy called Velupillai Prabhakaran, they knew there was no way of achieving their objectives by being nice. They perfected the art of guerrilla warfare, living in the jungle and pouncing on their prey at opportune moments, only to melt away again before reinforcements arrived. They recruited soldiers from throughout Tamil Eelam and focused on children to indoctrinate them at an early phase. They learned to survive in rough conditions on basic food and to absorb devastating attacks. They targeted Sinhala civilians far away from the war zone with suicide bombs — back in the ’80s, before anyone else did. They tunneled deep underground to withstand air raids. They even developed their own little air force and navy, complete with a homemade submarine. They exulted in a cult of martyrdom, self-sacrifice and martial heroics.

The war raged on, mostly monotonously, for 2 decades. The Tigers were never powerful enough to pose much of a threat to the Sinhalas, but they were too tenacious to be defeated, either. India, eager to play a role as regional hegemon, intervened in 1987 with a peacekeeping force meant to separate the 2 sides long enough for talks to be held. It didn’t work: the Tigers saw the Indians as uninvited interlopers and attacked them, while Sri Lanka stood back and let them die, anxious for their departure as well. After only 3 years and no progress with those talks, the Indians left, and Indian prime minister Rajiv Gandhi paid for the whole episode with his life (he was assassinated in 1991 by a Tiger agent).

The Tigers put up a good fight, and gained fame/infamy internationally for their intensity/cruelty, but they were always on the defensive. Sri Lanka simply had too many resources. After 2005, when a hardline president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, was elected, their fate was sealed. He bulked up the army with a massive recruitment drive until Sri Lanka had a military 30 times bigger than it was in 1983. He attracted military aid from a random mix of friends (China, Iran, Israel, Pakistan, Russia) tired of the fighting and waiting to invest in Sri Lanka’s development. He stocked up on ammo, vehicles, and new weapons like multi-barrel rocket launchers.

Norway and Sweden had negotiated a ceasefire in 2002, but it was tense and no one really wanted to stop fighting yet. By 2006, the war was back on, and reached its final phase. The army was ruthless and held the territory it reclaimed from the rebels. Aid from sympathetic Tamils in India was interdicted. Since Sri Lanka is an island, the Tigers had nowhere left to escape. By May 2009, they were cornered on a beach in the northeast with no hope of a comeback. Prabhakaran and his remaining groupies died in a blaze of glory, or after surrendering, or while trying to escape by sea — journalists were barred from the war zone, so once again the true story is unknown. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were trapped in the crossfire, and many of them died. But with a finality rare among long-running guerrilla wars like this, the Sri Lankan Civil War was over. The Tamil Tigers and their regime passed into the history books.

The territory of Tamil Eelam at its maximum extent.

CURRENT SITUATION

There was some disgruntlement among the Tamil community about their government’s ignominious trampling, but for the most part the war really did end suddenly. After 26 years of mostly continuous fighting, Tamils were exhausted, and Sri Lanka has undergone a demographic shift that favored more sober 30-somethings and not fiery, violent 20-somethings. Northern Sri Lanka went through the process of rebuilding. Landmines are gradually being removed. IDP (internally displaced persons) camps are being emptied. Shattered infrastructure is being mended or rebuilt.

Peace, and all its attendant blessings, has dawned on Sri Lanka. Tourism has always favored the south, but links with the former Tamil Eelam are now rebuilt. Foreign investment is pouring into the Tamil cities of Jaffna and Trincomalee. Kids are going back to school instead of boot camps in the jungle.

But there’s still an air of disquiet and sadness in the Tamil lands. The war grew out of Tamil disenfranchisement, after all, and little has been done to reverse this since the war ended. The government is still Sinhala-dominated. Sri Lankan society still promotes a Sinhala-dominated national discourse that dismisses minorities and crows over the Sinhalese victory. Buddhist monks, like their counterparts in Myanmar, stoke a siege mentality and a chauvinistic interpretation of Buddhism. The military is still thick on the ground in the north, and valuable properties expropriated from Tamils during the war remain in its hands. The language barrier is still high, and since the government, police, military and courts are so Sinhala-dominated, many Tamils can’t even understand them unless both sides speak English.

The most obvious positive step in terms of reconciliation so far was the 2015 election of Maithripala Sirisena, mostly because Rajapaksa and his brothers were behind the most egregious policies. The military presence in the north has become less stifling, and thousands of Tamils are no longer abducted in the middle of the night. Sri Lanka’s constant denial and protests over any international criticism of its conduct of the war, which by most accounts involved torture, massacres of civilians, bombings of hospitals and rape, have abated, and Sirisena has promised to allow a more impartial accounting of war crimes. Tamils are allowed to talk openly about their problems, and a Tamil press has revived.

But the fundamental problems remain. Sinhalas continue to see Tamils as foreigners and cling to their own self-congratulatory narrative. Riots in March between Sinhalas and Muslim Tamils show that religion remains a flashpoint and source of distrust. Tamils traumatized by years of carnage find it hard to see their southern neighbors as friends. The military still occupies the north, jails dissidents without charges, and gets subsidies in its businesses there that crowd out locals. Sirisena shielded a popular general, Jagath Jayasuriya, from war crimes charges to cater to his Sinhala base. For now, Tamils are too worn out and beaten to raise much protest, but if their grievances are not heard, political conflict and war might erupt again.

Two very different perspectives on the war.