Lula visits Tanzania in 2010. Image source: AFP/Getty Images

The bond between the countries of North America (Canada and the USA) and Europe is one of the world’s strongest and most consequential. Historically, culturally, and linguistically, North Americans are intimately bound with their European kin. Since the beginning of European settlement there, North Americans have flocked to Europe on travel, study or work, and there is a continual fascination with the other side of the ocean. Through the institutional architecture of NATO, North America and Europe (which is most of what is called “the West”) generally move in lockstep on diplomatic issues.

This post, though, is not about that relationship. Instead, it’s about another key transatlantic bond, but one that’s been continually ignored: the one between Brazil and Africa.

BACKGROUND

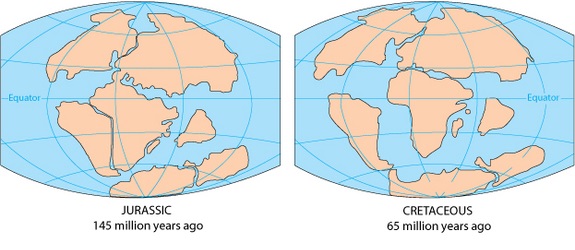

Brazil and Africa have very strong ties. Start with geography: South America and Africa used to be one landmass, as evidenced by how far east Brazil bulges and the huge indent along Africa’s coast (the Gulf of Guinea). The sea between Natal (in Brazil) and Liberia (in West Africa) is still the narrowest part of the Atlantic except for the northernmost part where Greenland fills in the gap. There is a murky tradition in West Africa of the medieval Empire of Mali voyaging across the sea to trade with the opposite coast and maybe colonize it.

Gondwana, the super-continent also including modern India, Australia and Antarctica, broke apart in the age of the dinosaurs. Image source: U.S. Geological Survey

But as usual, it was Europe who bound the 2 regions together for good. Portugal sailed around Africa’s coast in the 1400s on its way to the riches of Asia, seeding it with trading posts along the way. Eventually an explorer found the part of Brazil that bulges out. Like its Spanish cohorts, Portugal vanquished the native Brazilians and seized the coastline for itself. Brazil turned out to be a rich and bountiful prize, loaded with lumber, gold and diamonds. Portugal needed lots of labor to work its colony, and the native peoples were dying out from imported diseases. And the Portuguese themselves didn’t want to do it.

… So they turned to Africa, where thousands and thousands of people were being captured and brought in chains across the ocean to work the sugarcane plantations of Brazil. The Caribbean may have been the main destination, but Brazil was the biggest single colony: over the 300+ years of the transatlantic slave trade, around 5 million Africans were brought to Brazil, or around 38.5% of the total. They stripped Atlantic Brazil of its jungles, mined its minerals, hacked its sugar, and later plucked its coffee. Any kind of manual labor, from unloading ships to housekeeping, became the province of black slaves. And because slaveowners were rarely hesitant about raping their property, Brazil grew into a mixed-race society united by the Portuguese language. (Not all of this traffic was one-way, by the way; Brazilian slaves could buy their freedom, and some of them returned to Africa afterwards, where they brought valuable technical skills and commercial expertise to an area mostly cut off from international trends.)

Slavery in Brazil was abolished in 1888, but it left a permanent mark on the country. Most obviously, it gave it a permanent black underclass and a social hierarchy that closely paralleled skin color. But the African influence on Brazil was profound. For example, feijoada, Brazil’s national dish, is a black bean stew strongly influenced by Portuguese tastes (it uses linguiça sausage) but incorporating weird cuts of meat like pork tails and feet, which were the scraps given to slaves. Brazil’s national music, the samba, is directly descended from African styles and was pioneered in the early 1900s by black musicians. African beliefs inspired a uniquely Brazilian religion, Candomblé, which worships personal deities and has its own rituals. The northeastern part of Brazil — the part that bulges out towards Africa — is predominantly black and has the strongest African cultural influences.

Despite this, Brazil’s elite snubbed Africa and links with it after abolition. In thrall to the racist ideology pervasive among whites in the early 1900s, they instead tried to whiten Brazil’s demographics by encouraging immigration from Europe and further race-mixing in the belief that future generations would be lighter-skinned than the current mix(the branqueamento policy). The first part of this policy succeeded, and Brazil now has large populations from Italy, Germany and Eastern Europe. Black people, however, never really went away.

By the 1960s, overt racist ideology was dying away, and African colonies were gaining independence. Brazil’s presidents began paying more attention to Africa and forging alliances with the new countries. But concerted outreach to Africa remained lacking for many decades; Brazilian dictators prioritized the relationships with Portugal and South Africa, that is, an intransigent colonial power and a racist regime. The dictators also embraced a generally conservative world outlook, which didn’t appeal to Africans, who prefer more revolutionary, left-wing stances.

CURRENT SITUATION

These days, Brazil is experiencing a renaissance in its connections with Africa. It began under President “Lula” da Silva, who took a genuine interest in the continent. During his 8 years in office, he visited Africa 28 times, taking in 21 different countries there, and doubled Brazil’s embassies there from 18 to 37. His successor, Dilma Rousseff, carried on the momentum, albeit to a lesser extent.

As usual, the core of Brazil’s diplomacy with Africa is investment and technical cooperation. African countries are rich in minerals and oil, and Brazil has the mining companies to exploit them. Brazil also has a bevy of construction firms ready to build up African infrastructure — Odebrecht, Andrade Gutierrez, OAS, Camargo Corrêa — and well-educated engineers and scientists with the expertise to research new drugs, crop varieties, and other things of benefit to Africans. On the other hand, trade plays a growing role in the relationship; it’s shot up from $3 billion in 2000 to $26 billion in 2012, and Brazilian companies now use Africa as a market for their (cheaper) consumer goods. Brazilian telenovelas (soap operas), with their rags-to-riches stories and melodrama, are popular in Africa.

Brazilian TV is most popular in Angola and Mozambique, which are Brazil’s main partners in Africa. This shouldn’t come as much of a surprise: they were also Portugal’s main colonies in Africa (the other ones being Guinea-Bissau and the islands of Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe). Many Afro-Brazilians originally came from these lands, especially Angola. They are also struggling to rebuild from devastating civil wars and need sustained infrastructure investments. But Brazil is moving on to other countries that don’t speak Portuguese and importing Nigerian oil (which is better suited to Brazil’s refining processes), building roads in Kenya, and selling cluster bombs to Zimbabwe.

Brazil is far from alone in supporting African development, and it lags behind the West and China in the scope of its involvement, but it has several key advantages. For one, there’s its shared history and a certain sense of familiarity with African culture, but more importantly, it’s a tropical country. Its agricultural specialists figured out how to grow crops like cassava, soybeans, and cotton in the cerrado (Brazil’s parched savannah), so its techniques are relevant for other tropical countries searching for ways to grow new crops, create more farmland and increase their yields.

Brazil also represents sort of a development success story. It has long festered in poverty and underdevelopment, and its chronic hyperinflation made it depend on IMF bailouts to keep afloat. It is now a member of the BRICs, the most powerful and important emerging economies, and until recently had money to throw around overseas. It still has a huge, struggling underclass, but its welfare program, the Bolsa Família, has been a roaring success, lifting 40 million Brazilians out of poverty since its inauguration in 2003 at a cost of only .05% of GDP. Proud of its achievement, Brazil has held seminars on the program and other welfare initiatives for Africans grappling with much worse poverty and invites delegations over to see conditions for themselves.

Politically, Brazil isn’t the stern conservative oligarchy it once was. The ruling party, the Worker’s Party, is leftist and preaches Third World solidarity. For all of its close links with the West, Brazil still feels a lot of bitterness toward it as a result of being ignored, dismissed, and indebted for much of its history. It sees the “global South” as having a common bond: resistance to Northern oppression and a struggle to survive in a Northern-run economic system. And as by far the largest and most important country in the Southern Hemisphere, Brazil is in a natural position to lead — and increasingly knows it.

This is most likely the main reason for Brazil’s increased attention to its eastern neighbors. Consumer markets and natural resources are great, but other markets are much more lucrative and Brazil has plenty of resources of its own. Sentimental and cultural ties are also important and give Brazil an edge over some of its rivals, but it’s hard to tell how much this is the result of Lula’s personal feelings and whether it will endure after the Worker’s Party is swept out of office. But politically, Brazil needs Africa. It has ambitions to be a Great Power someday, and Latin America won’t be enough of a sphere of influence. Africa remains the most struggling part of the world and the area in most dire need of sustained investment and development, and it lacks a hegemonic power that could feasibly be a rival for Brazil, so it will remain the continent Brazil must win over if it wants to demonstrate Third World solidarity and maybe even a seat on the UN’s Security Council (the important part) someday.

So far, Brazil is doing well. The West remains tainted or at least a little suspect in African eyes; even if well-intentioned, Westerners rarely face the same crippling institutional problems and hurdles to development that Africans do. China and India are rising powers with development cred, but they are also seen as distant foreigners motivated primarily by self-interest and sometimes rapacious in their greed. Brazil actually hires Africans, builds urban housing for the poor, consults with locals, and trains them to manage their own enterprises. Most of the resources it extracts still flow out of Africa, and Brazilian companies are still corrupt and destructive like other Third World firms, but all in all Africans trust Brazilians more.

Back in Brazil, African heritage is becoming more and more widely accepted and celebrated. Capoeira, the dance form invented by slaves that doubled as martial training, is now considered Brazil’s most unique contribution to martial arts. Salvador’s heavily African-influenced Carnival celebrations rival Rio de Janeiro’s bigger, more famous ones. Black Brazilian artists and musicians incorporate more and more African influences into their work. Yet Brazil’s elite continues to value European culture over African, and the vast majority of blacks remain poor manual laborers. Whether Brazilian business will get more interested in Africa if more blacks go into the business class remains an open question.

Brazil continues to face enormous and daunting problems. The legacy of its slaveholding past has not gone away, and racism remains a fact of life there. It is also grappling with an economic slowdown that is forcing businesses and the government to cut back on all fronts; it may even have to seek funds from the IMF once again. (Africa is suffering from a similar slowdown, mostly caused by falling demand for commodities.) Many of Brazil’s biggest companies have been tarnished by a corruption scandal focusing on its state-owned oil company, Petrobras. But depressions don’t last forever, and Brazil remains a development success story and a natural leader for the Southern Hemisphere. Continued Brazilian engagement in sub-Saharan Africa should bring benefits to both sides.

One more for the road.