German Chancellor Angela Merkel with former French President Nicolas Sarkozy. Image source: REUTERS/Yves Herman

It’s been called the most serious crisis facing Europe since World War II. It’s paralyzed the continent, wafting over its countries like a miasma and keeping its leaders awake at night for years. It’s led to disillusionment, confusion and despair for an entire generation of Europeans, uncertain of their countries’ futures — and their own. It’s brought the whole notion of European solidarity, and even the European Union itself, into doubt. It shows no sign of ending and generates more and more bitter discord and bickering each time it hits the headlines.

Yet for all its huge significance, the details of the euro crisis remain sketchy to many outsiders. In particular, America has remained aloof from it, making it the most serious postwar international crisis without its involvement. But it’s a really big deal, and understanding it is critical to understanding the future of one of the world’s economic engines, and therefore to the world as a whole.

And so I present to you my account of the euro crisis, in all its sordid, depressing glory. Fair warning: This post is even longer than usual. I didn’t want to get into too much detail, but I wanted to do a complex topic justice. So put this off until you have some free time, then pull up a comfy chair, pour a glass (or mug, or cup) of your favorite European beverage, and “enjoy.”

BACKGROUND: THE EU

Although the main perception of European history is of a collection of squabbling, shifting countries eternally in competition with each other, there has also always been a notion of European unity. This mainly dates back to the Roman Empire, which mostly ruled the southern part of Europe (Germany was mostly omitted) but set the standards for European culture linguistically, politically, artistically and religiously. Its memory lived on in Karl the Great’s Frankish Empire (700s/800s); although that was a smaller, less advanced empire, it included France and Germany (modern Europe’s core) and perpetuated a notion of a unified Western Christendom for a long time. Later, various conquerors tried to unite Europe, and some came very close. The closest Europe came to unity, however, was under Adolf Hitler, and that was not an experience most Europeans look back on fondly, to say the least.

After World War II, Western Europeans became interested in a united Europe once again. This wouldn’t be an empire or a mega-nation, though; they had in mind a federation of nation-states on good terms with each other and governed by a set of institutions on top of their national governments. These statesmen first wanted a “European Defence Community” merging national armies, but that was decided to be too close to NATO (a bigger military alliance dominated by America) and infringed too much on national sovereignty. So instead, they hit on a European Economic Community: a free-trade zone and customs union. First they started with coal and steel, then they moved on to atomic energy (which was the fuel of the future in the 1950s), and then they formed a formal union in 1958 between France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg — the core nations of western Europe.

As you can tell from the name, the European Economic Community was always first and foremost economic: it was meant to standardize economic regulations, promote the free flow of capital and labor, and encourage trade among its members. But the political goal of its founders remained: a stronger political union among the European countries. They wanted a Europe where its people saw themselves as Europeans first and foremost, where Italians and Britons and Germans all congregated with ease, where people had an interest in improving other countries and forging tighter bonds with them, even if they were historic enemies. So the EEC had quasi-governmental institutions: a Council of European heads of state, a Commission that enacted laws for the community, and a Parliament that debated matters of common interest and elected members of the Commission. Brussels, its capital, grew into a bureaucratic hive of technocrats and officials dedicated to European union. The community expanded to incorporate Britain, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Denmark and Austria.

The notion of a single common currency uniting the advanced economies of Europe gained serious traction in 1990, when as a result of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Communist Bloc, Germany was reunified. Although West Germany had been the economic powerhouse of capitalist Europe anyway and had a much higher population than the East, other Europeans (especially British prime minister Margaret Thatcher) fretted that a reunified Germany would dominate the continent once more, and even set out on another campaign of conquest. To bury any of these ideas, the EEC agreed to take the decisive step marking its transition to today’s European Union (EU): surrender (most of) its members’ currencies and unite under a new one: the euro. It was the logical conclusion to all the economic standardization of the previous decades, and with all these sometimes bickering countries united under a common monetary system, any political friction would be tamped down — and Germany in particular would be restrained.

Sadly, it didn’t quite work that way. The euro is regulated by a Central Bank (based, significantly, in Frankfurt, Germany), but the different countries in the eurozone get to choose their own budgets and how much of the money to use. To join the eurozone, EU countries were tested for budgetary discipline, but there was a lot of fudging. The political desire for a substantial eurozone outweighed economic worries about countries being spendthrift. Italy boosted its figures by simply selling gold reserves from one government branch to another, but as one of Europe’s biggest countries and a founding member of the EEC, leaving Italy out of the eurozone would make it look too limited. And despite the strengthened political unity brought by the EU, nations were still mostly responsible for their own affairs. Helmut Kohl, chancellor (prime minister) of Germany, admitted that a monetary union without a political union was “a castle in the air,” but the general mood was all about peace and harmony and reconciliation and brotherhood and “europhiles” were determined to strike while the iron was hot.

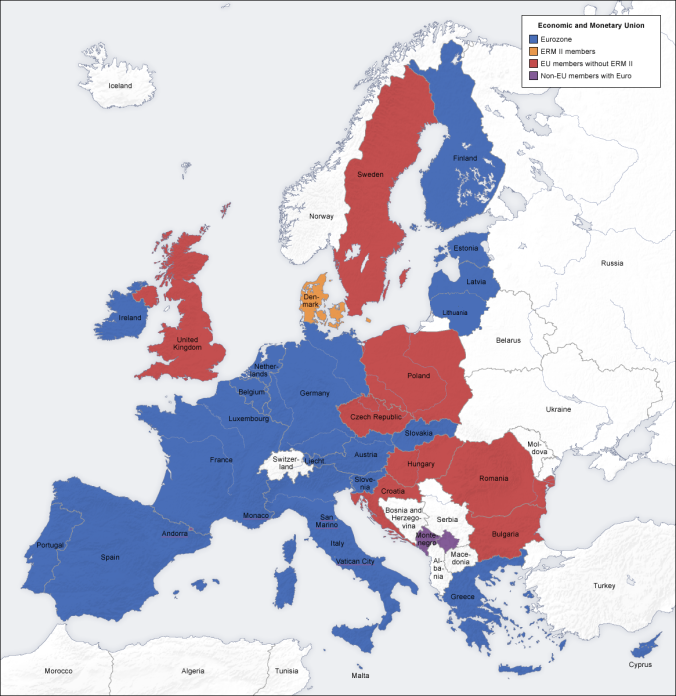

Blue countries are in the eurozone. Red countries are in the EU, but not the eurozone. The purple countries have adopted the euro but aren’t in the EU. Denmark has its own currency, but it’s pegged to the euro.

Despite the misgivings and doubts of most economists, some politicians, and an awful lot of the public (including 60% of Germans!), the euro was introduced in 1999. After an awkward adjustment period, it seemed to be a roaring success. The eurozone was united by a common interest rate, which meant money was suddenly easy to access for investors throughout the eurozone. The nations of southern Europe — Spain, Portugal, Italy — went on a borrowing spree; in Spain the ’00s were called “the years of concrete.” New airports, hotels, conference centers, roads, ports, and museums sprang up, even in rural backwaters. Spain finally got a modern railway system. A real estate bubble fueled unsustainable housing construction, especially in Ireland, whose spectacular economic growth (9.5%) in the early ’00s made it known as “the Celtic Tiger” (in reference to the “Asian Tigers” that had boomed in the ’80s). The euro fueled more consumption and trade among its member states, so whatever misgivings Germany had about the spending frenzy were neutralized by the profits its manufacturing sector was making.

For about a decade, the euro was hailed as a blessing for the comparatively disadvantaged parts of Europe and an ingenious tool for leveling the economic playing field. But reality caught up soon enough.

BACKGROUND: THE EURO CRISIS

In 2008, the bottom fell out of the dance party stage. Lehman Brothers and other big American financial institutions collapsed as their risky subprime mortgage loans went sour. The fraud and chicanery that made up a lot of the lending and finance industries was laid bare. It had transatlantic effects: Anglo Irish Bank, one of Ireland’s biggest, was heavily exposed to the subprime mortgages and had to be bailed out by the government. For a few scary months the global economy trembled, with bank runs looming, investor confidence demolished and the stock market tumbling. Only a concerted, transnational government intervention and an aggressive American stimulus in 2009 staved off a global depression.

Unfortunately for Europe, this only proved to be the catalyst for a bigger, more prolonged crisis. The problem was Greece. Despite being an eastern European country, Greece had avoided Soviet domination, and in 2001 it joined the eurozone. This was already a bit of a stretch; economists called the head of Greece’s statistical agency “the magician” because “he could make everything disappear. He made inflation disappear. And he made the deficit disappear.” And once in the euro, Greece pulled the same shenanigans as the other countries: staggeringly high borrowing and property values with little productive investment. But Greece was worse because it has a culture of shirking tax payment, defrauding the state (bogus disability benefits, pensions paid to the dead, etc.), a bloated public sector (about 20% of the working population), corruption, political favoritism, and falsified statistics. (It also had the Olympic Games in 2004 to pay for.) During the ’00s boom it had managed to keep the full extent of its financial mess a secret, but when Giorgios Papandreou became prime minister in 2009, he learned that the national deficit wasn’t 6.5%, but 12.7%. Technically countries in the eurozone were supposed to have a deficit of 3%. Greece’s debt equaled over 120% of its GDP.

Papandreou, to his credit, was shocked and appalled at the accounting mess and took measures right away to cut the deficit. But the situation soon spiraled out of control. With the charade exposed, international investors and speculators no longer had confidence in the Greek economy; its borrowing costs increased. It became obvious that Papandreou wouldn’t be able to pay off Greece’s staggering debts, especially with the economic contraction Greece was suffering. So in 2010, the EU broke its own rules against countries being responsible for foreign debts and bailed out Greece with €110 billion (with input from the International Monetary Fund, an American-based international lender).

But by then investors had realized how fragile the eurozone actually was. Multiple countries (Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain, the so-called PIGS) had run up crazy debts and there was no plan to pay them off. A mood of panic seized financial markets on May 7, 2010, and investors started pulling their money out of Europe, seeing the whole eurozone as a naked emperor. Another global financial meltdown, far more serious than the one that struck Wall Street, was imminent. Over a harrowing weekend, the eurozone’s finance ministers and heads of state met in Brussels to figure out a rescue plan. At one point they were literally racing against the Earth’s rotation, so fearful were they of what would happen when the markets opened in East Asia at daybreak on Monday. They ended up by creating a bailout fund of €750 billion for any future debt crisis, again with input from the IMF. France hoped this financial firepower would reassure jittery financiers.

The price for the bailout, mandated by the EU’s true powerhouse, Germany, was austerity. This meant mandatory pension, spending and wage cuts, public sector layoffs, and tax hikes. Germany was miffed that Greece had partied while Germany had reformed its economy and now was expected to pay the bill. Austerity was supposed to reduce Greece’s debt while setting an example for other profligate countries to reform or else. But the program strangled Greece’s economy, and Greeks reacted with fury, rioting in Athens and firebombing a bank.

This process played out again in Ireland, which had never recovered from the 2008 collapse, but had instead slumped economically, with banks racking up ever higher debts and borrowing costs shooting up to 8.89% by November 2010. The government’s assurances that it could pay off its debt looked more and more threadbare, and investors started packing up and moving funds to Britain. Irish Finance Minister Brian Lenihan, dying from pancreatic cancer, spent his last year fighting in vain to fend off impatient eurocrats and foreign leaders, who were insistent that Ireland needed to accept a bailout to keep the eurozone from collapsing. Ireland finally bit the bullet on November 28, accepting an €85 billion bailout. The drama played out again in Portugal early in 2011, where despite repeated denials and assurances that everything was fine and things would get worked out on their own, it buckled and accepted a €78 billion bailout.

France and Germany are the 2 countries at the center of the eurozone; they set EU policy and represent its 2 most powerful economies. But a clash between Nicolas Sarkozy, France’s president, and Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, aggravated the euro crisis even more. Partially it was a matter of incompatible personalities; Sarkozy was flashy and charismatic while Merkel is stodgy and dull. But they had fundamentally contrasting goals: Sarkozy was dedicated to the ideal of Europe at all costs and wanted the EU to do whatever it took to hold the eurozone together. Merkel is more cautious and thrifty and worried about the consequences of giving profligate countries a blank check to waste. Sarkozy insisted on the bailout fund to stabilize the eurozone and prodded the European Central Bank to buy bonds even though this infringed on its political independence, but Merkel and her finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, demanded austerity measures as a guarantee.

By 2011, though, the crisis had expanded beyond relatively marginal countries like Greece, Ireland and Portugal. As we have seen, Spain also went on a spending spree in the boom years. What if it defaulted? What if Italy, always a somewhat dodgy economy with lots of loose regulation, defaulted? Major international banks and financial institutions had lent to these countries. They have about 100 million people and are pillars of the eurozone. How could the EU possibly pay off their debts?

Sure enough, in the summer of 2011, the markets turned their fearful gaze to Italy, convinced that its debt, unemployment numbers and tepid growth were a recipe for disaster. Its borrowing costs inched inexorably upward, reaching 6.2% by November, and putting its government in a financial squeeze. France and Germany demanded that Silvio Berlusconi, Italy’s notoriously sleazy leader, push through the kind of reforms everyone else was grappling with: a rise in the retirement age, a crackdown on tax breaks, labor market deregulation, and wage and pension cuts. Berlusconi waffled, hobbled by a fragile domestic political situation. The screws were tightened, and the European Central Bank refused to buy Italian bonds, forcing its borrowing costs up and up. With Sarkozy and Merkel no longer taking him seriously and his own allies deserting him, Berlusconi resigned on November 8. He was replaced by Mario Monti, an unelected economist with strong backing from the EU thanks to his austerity credentials. Now the EU was in the position of toppling and installing prime ministers.

Meanwhile, the austerity program Greece was forced to undertake was practically poisoning its economy. With massive public sector layoffs and high unemployment (16%), government revenues inevitably dropped, forcing Papandreou to cut government services even more. By the summer of 2011, Greece had no choice but to beg for another bailout, which it got — €109 billion this time. And of course, Germany demanded more austerity as a result.

The bailout terms provoked such an enraged reaction in Greece that some feared that the country was on the verge of breaking apart, as a society and politically if not geographically. Mindful of how contentious it was among his people, Papandreou decided to put the bailout deal to a referendum. Merkel and Sarkozy were enraged in return: they had just negotiated tougher terms for bankers invested in Greece that forced them to give up 50% of their loans, saving the country €100 billion. They howled at Papandreou and convinced him to give up the idea. Humiliated and exhausted by the experience, he resigned on November 10, to be replaced — like Berlusconi before him — by an unelected eurocrat: Lukas Papadimos, the former vice president of the European Central Bank.

But the Greek Parliament still had to pass the austerity measures that came attached to the bailout. They were so onerous, and Greece was already so paupered, that destructive rioting accompanied the vote. Parliament passed the deal anyway, but Greece remained chronically short of funds. An election in May 2012 unnerved Papadimos because no party won a majority; the country needed a stable government to stay solvent. It also unnerved him because anti-austerity parties did well, prompting a capital flight. In a second round in June, Conservative leader Antonis Samaras won, but with only 40% of the vote. It was becoming obvious that Greeks were not behind their own government.

Britain played a minor yet annoying role in the squabbling. It has always been a reluctant and hesitant member of the Union. It only joined in 1973, some time after the other major Western countries, and stayed out of the eurozone. Britons are nervous about EU encroachment on their sovereignty; they have long played a role in European politics but have always tried to stay aloof and detached from the thick of things. So they stayed out of the bailout negotiations and refused to contribute to the bailout fund, but intervened to ask for financial deregulation to protect the City of London (Britain’s financial hub). Merkel and Sarkozy, deep in the trenches of haggling and persuading and lecturing countries about following the rules, weren’t about to let a more advanced economy like Britain tweak the rules to benefit the bankers that had gotten Europe into the mess in the first place. Later, British prime minister David Cameron announced a referendum in 2017 to pull out of the EU entirely.

Spain did its best to stave off the stranglehold of IMF budgetary oversight, with its new prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, taking tough austerity measures that crippled the Spanish economy to see off EU nagging. But by 2012, the Spanish banking sector, saddled with busted loans and mortgages from its housing and construction bubble, was on the verge of collapse, and Spain was forced to discreetly seek a €100 billion bailout on June 9. It ducked the cataclysm of a default, but felt the pain of youth unemployment and recession and a government starved of funds to carry out basic services like paying its employees.

Meanwhile, France gained a new president, François Hollande, from the Socialist Party. Although France — as a country with an unsustainable welfare state and a ‘Mediterranean’ cultural outlook — had always been more sympathetic to the debt-ridden southern countries than Germany, under Hollande the tilt became pronounced. He denounced austerity as medicine that was killing the patient and preached solidarity with fellow Europeans. Merkel remained convinced that governments had to do their part to be fiscally responsible and carry on with reforms or the euro crisis would go on and on.

As the eurozone’s economic powerhouse, largest country and most fiscally responsible government, Germany now called the shots. It and Merkel in particular are behind the EU’s tough austerity policies and bailout packages. Yet Merkel has also been irked at the role banks and financiers have played in the crisis. They were the ones who invested in risky government debt in the first place, yet they were also the ones who benefited from the bailouts. In October 2010, in the aftermath of the first Greek bailout, the Deauville Agreement forced banks with risky debt to accept minor losses to their loans. It was the result of Franco-German agreement, but it enraged Greeks and Irish who realized how unlikely it would be for investors to trust them in the future.

For the most part, the people in debtor countries reacted to the crisis and its associated austerity docrtine with howling rage. Protests became a regular occurrence, especially since the youth were hit hardest by the ensuing recession (around 40% were unemployed in Spain and Greece at its height). The cushy benefits and glitzy lifestyles of the boom years were gone. In their place were dirty streets, abandoned houses, deserted towns, bums, and pervasive hopelessness and despair. Greece in particular is suffering a Great Depression of its own, with urbanites returning to rural communities to take up farming, soup lines stretching for blocks, and scavengers picking through landfills and poorly guarded empty lots. The government tried its best to drum up revenue, but by 2011 Greeks were revolting (taping over subway ticket machines, dismantling toll booths on roads, etc.).

As mentioned earlier, America has been rather insignificant in the crisis. Although prodding from its Treasury Department for a clearer picture of the EU’s finances in 2009 helped ignite the crisis, for the most part it’s watched from the sidelines, occasionally hectoring the EU to deal with the crisis as quickly and as best it could to prevent a global depression. Other non-European countries were mostly reduced to the same role, although those with big foreign exchange reserves now found themselves in a newly powerful position as the potential financial lifelines of the EU. China, in particular, with its over €3 trillion in reserves, has gained enormous leverage over Europe, and has used the crisis to get more access to European markets in exchange for buying up risky bonds.

Luckily, by 2013 the worst of the crisis had passed. Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy were on the road to recovery. The giant capital flight out of Europe that would have sounded the death knell for the euro had been avoided. Greece was reluctantly following the austerity program the EU and IMF demanded. Cyprus collapsed and was bailed out with a controversial tax on bank deposits effectively punishing ordinary citizens, but it had a bloated financial sector funded mostly by crooked Russian businessmen, and Germany was adamant that Cypriots be punished for serving them.

But all in all, it seemed that the eurozone was once more on the path to stability. The days of financial panic and cantankerous bailout negotiations were in the past. Right?

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble argues with his Greek counterpart, Yanis Varoufakis. Image source: AP

THE EVENTS OF 2015

Unfortunately, Greece continued to struggle with its creditors’ demands. With so little money sloshing around its economy, its debt only grew and grew, and there wasn’t much hope for economic growth that could push it out of its ditch. Instead, despair and frustration only built. Dire times called for dire solutions, and fringe parties like Golden Dawn, a hard-right group that mixed public charity initiatives with Fascist-style attacks on foreigners, found a ready audience. The government struggled along with little popular support; it was seen as cowardly and beholden to banks and Brussels.

The biggest fringe beneficiary of this climate was SYRIZA, or the Coalition of the Radical Left. It originated as a bunch of student radicals who would meet in cafes and kvetch about the inequities of capitalism and the hopelessness of austerity, but gained a following as the recession bit harder and deeper. Its leader, Alexis Tsipras, relentlessly attacked Samaras as a dog of the European Central Bank willing to sign away Greece’s future to appease the stern Germans. Rumblings of discontent from the EU and a stock market plunge only seemed to embolden the Greeks, who voted SYRIZA into power in January.

Thus began a spring of frustration and acrimony. Tsipras was elected on a promise to renegotiate Greece’s austerity program. He wanted to be able to rehire public workers, restore public services, and increase pensions. He calculated that Greece was too valuable to the eurozone for the creditors to stand firm. Unfortunately for him, Europe has calmed down somewhat from the crisis peak in 2010-12, and Germany no longer felt as desperate to keep Greece in. So irascible “negotiations” that went nowhere were the result.

Tsipras, increasingly desperate and fearful of not fulfilling his promises, even dredged up the issue of Germany’s World War II-era reparations payments, which have still not been paid off in full. It played into the popular perception of Germans as brutal, oppressive Nazis, but reminding Germans about the war is a surefire way to ruin the mood, and Merkel continued to stand her ground. Tsipras also went to Russia to suck up to Vladimir Putin and beg for money (as Cyprus had done in its crisis), but this accomplished little, although it did anger the EU even more given its disapproval of Russia these days.

By June, the crisis had come to a head once more. Greece ran out of money. Like Cyprus in 2013, strict withdrawal limits were set on ATMs. Economic activity ground to a halt. The central government was plundering local government money. It became obvious that once again, Greece would need a bailout to pay off its debts (€320 billion). And in order to get that bailout, it would have to swallow more painful medicine — pension cuts, spending cuts, more taxes. Tsipras haggled with his creditors and with his own parliament. A default deadline loomed at the end of the month.

The drama reached its peak when Tsipras, jittery about the potential political fall-out from forcing another hated austerity program on his people, followed in Papandreou’s footsteps and held a referendum on the bailout terms on July 5. After a week of frenzied and impassioned campaigning, Greeks rejected the terms by 61%.

The experience had brought Greece to the edge of its membership in the eurozone. Relations with Germany had plunged so far that both Schäuble and Yanis Varoufakis, Greece’s finance minister, preferred “Grexit” (Greek exit from the euro). Editorials swirled about the possible consequences of this. With the bailout rejected, it seemed like the only option left.

… And yet, humiliatingly for Tsipras, Greece agreed to bailout terms anyway only a week later. They were even harsher than the previous terms and relied on unrealistically optimistic forecasts for Greek economic growth and structural reforms. He justified it by saying that it was necessary to keep Greece in the euro — still somehow the preferred option for most Greeks, despite the referendum vote. And frankly, Greece has always been in a bad position, because it desperately needs money, and all the grandstanding and threats it can make don’t change that central fact.

EUROPE IN DESPAIR

Since the summer, Greece has muddled on. An election on September 20 returned SYRIZA to power in a coalition with a far-right party called the Independent Greeks. Tsipras remains in power, although his support has eroded, either because he kept Greece in the eurozone (Varoufakis has resigned, for example) or because his reckless negotiating style didn’t help the country. Greece remains mired in recession, with strict capital controls to prevent banks moving their funds out of the country, 25% unemployment, hungry schoolkids and a complete destruction of any trust in the government’s word regarding its finances.

Despite ongoing struggles with unemployment and slow growth, the other PIGS have recovered and accepted their fate with less fuss. But discontent remains strong. Podemos, another stridently anti-austerity party, is now Spain’s 2nd-largest political party, and the Five Star Movement, Italy’s variant, gained about 25% of the popular vote in elections in 2013. Even in France, there is resentment over what is seen as German dominance of the debate within the EU.

Sympathy with Greece, on the other hand, is limited. Slovakia and Slovenia joined the euro just before the storm broke, and they had to accept budget discipline and spending restrictions to survive. Southern European countries are also irked that Greece has received so much attention and bailout funds while they have comparatively accepted their punishment grimly. Its failure to take tough measures like cracking down on corruption or freeing up the labor market make it seem spoiled and unreasonable.

Germany has mostly sided with its chancellor in the crisis. Merkel’s reelection in 2013 proves this. The general consensus is that Greece and other struggling economies deserve a bailout, but only if they do what Germany says they must do to reform their economic systems. But some Germans have grown impatient with throwing money at wasteful and grateful southerners, and there has always been pressure on Merkel to take a firm line. A new party, the Alternative for Germany, calls for an end to the bailouts altogether, and has attracted a following, particularly in the east.

On a grand scale, the crisis has exposed deep and worrying fault lines within the EU. Economic reforms and debt restructuring are one matter; the political calculus is another. The EU was formed in a love-feast mood of solidarity and international bonds. Countries were supposed to work together and come to agreement through consensus and mutual understanding. This ideal was always a little shaky, given strong minorities against further EU integration, but the euro crisis has effectively destroyed it. Germans are reviled in southern Europe as “occupiers”; protests with Nazi imagery applied to Merkel are common. Germans (along with Dutch, Belgians, Finns, and other northerners) scorn the southerners for their laid-back, unserious attitude towards society and finance. EU summits and negotiation sessions have devolved into lectures and temper tantrums.

As this blog post should have made clear, the euro crisis also exposed deep and worrying flaws in the euro itself. The European Central Bank may issue euros and set interest rates, but it can’t control spending. It is up to national governments to deal with the consequences of their actions. But since the EU binds the subcontinent together in a currency and trade union (and financial markets are thoroughly interlinked anyway), an economic collapse or financial crisis in 1 country can quickly spread to others. And why should ordinary taxpayers — in Germany, Cyprus, or wherever — have to pay for the folly of politicians and bankers? Most agree that the only solution that can keep the crisis from breaking out again and again is a tighter union, granting the Central Bank power over national budgets (which it already has informally).

But this would represent a serious breach of national sovereignty and probably give Germany an even greater say in European affairs than it already does. Even though the EU was formed to keep Germany submerged within a supranational union, the realities of economics and the euro crisis have made Germany the dominant power yet again. Germany’s stern talk of “moral hazard,” careful debt repayment and thrift has struck fear into southerners with no desire of giving up their siestas and slow mornings sipping cappuccinos. But the intent of the EEC’s founders was always to integrate Europe into a single federation. If the EU’s members can’t stand each other, how can it stay together?

This is probably the most serious of the problems that have grown out of the euro crisis. Worse than the anti-democratic installation of prime ministers and strong-arming budgets. Worse than the economic malaise and deflationary cycle that result from years of bitter austerity. The rancor and discord that the bailout dramas have provoked have shown that decades after the euphoria of the fall of the Iron Curtain, Europeans no longer trust each other and have diminishing interest in an ever-closer union. The euro crisis is the most prominent factor in this, but others, like the divisions over how to respond to Russian provocations in Ukraine and the recent wave of refugees streaming into the Balkans, have all contributed. As The Economist put it in a column titled “The Dark Clouds of Peace,” “the euro was built to foster friendship but is manufacturing misery instead.” The prominent American economist Joseph Stiglitz puts it, “Although the single currency was supposed to bring unprecedented prosperity, it is difficult to detect a significant positive effect for the eurozone as a whole in the period before the crisis. In the period since, the adverse effects have been enormous.”

The European Union was forged by a war and oppression-weary subcontinent dreaming of prosperity, brotherhood, unimpeded trade and travel, and freedom. It was supposed to point the way to a bright, progressive future above the petty politics of nationalism and bullying. Its official anthem is “Ode to Joy.” But can that mood be sustained in this kind of climate, when there isn’t even consensus on what to do with the monetary union, when EU officials visit indebted countries in secrecy out of fear of public rage, when referendums are discouraged because the EU is too afraid of what its own people will tell it?

Note: For those interested in learning more about the ins and outs of this dispute up to 2013, I recommend Gavin Hewitt’s The Lost Continent, which was an invaluable resource for me.