Sita rejects Ravana’s advances — not that it does her much good in the end. Image source: Nina Paley

The Ramayana, one of India’s 2 great national epics, tells the story of Rama, a virtuous king and incarnation of the god Vishnu, and his equally virtuous wife Sita. Rama is banished for 14 years to a forest, but Sita joins him out of loyalty and love. Her beauty and grace are known throughout the land, and eventually attract the attention of the demon lord Ravana. He kidnaps her and whisks her away to his island kingdom, where she rejects his advances and pines for Rama. After an epic journey, he finally comes to rescue her and slay Ravana — only to question her purity and force her to walk through fire to prove it. Even then, his subjects disrespect their queen, and Rama hears of a washerman who beats his wife for cheating on him, raging, “You think I’m like Lord Rama?” Rama addresses the issue by banishing Sita into the wilderness again, to live out her days and bear his children with a pious sage.

Sita is now worshiped across India as the ideal woman, with her chastity, devotion and beauty admired by millions of Hindus. The virtues she embodies, and the nature of her relationship with her husband, remain the model for Indian women millennia after the Ramayana.*

That’s not to say that nothing has changed. In colonial and precolonial times, women were sometimes reduced to slave-like status. They were married as little girls to men they didn’t know, thanks to marriages arranged by their parents. Their main role was to serve their husbands (and before that, their fathers) and stay secluded in the home. They were not expected to walk next to their husbands, call them by name, or look them in the eye. Should their husbands die first, they were denied his inheritance and doomed to live in terrible shame. The honorable solution was to jump into their husband’s funeral pyre. The British were especially offended by this last one, and outlawed it; most of the other traditions decayed over time or were banned by the Hindu Codes passed in the 1950s.

Yet the status of women remains low in today’s India. If not slaves, they are still often treated as household servants. A Muslim-influenced tradition keeps many of them inside the house most of their lives. When in the presence of men other than their husband, they cover their faces. Gender segregation is standard for most activities. Women have few opportunities to socialize, other than outdoor tasks like fetching water or group activities like foot-dying. They are systematically excluded from “important business” even if they manage household finances and welfare in reality.

Image source: Ashok Sinha/Getty Images

Although polygyny (one husband, multiple wives) is a thing of the past, other marriage traditions endure. Girls are still sometimes married off when they are very young (like 8). Divorce is legal, but shameful and heavily discouraged, trapping many women and girls in unhappy arranged marriages. To offset the financial burden of a wife, her parents are expected to pay a dowry to the husband’s family; these can be crushingly expensive, including fancy items like cars and TVs for the upper classes or cows for the lower classes.

Girls are discriminated against from a young age; although education is a major problem for both genders in India, since many parents prefer to have their kids working rather than “waste” their time in school, girls are kept out of school more often. Even in school, teachers focus more on boys. As a result, the literacy rate for girls is only 65.5% — 16.5 points below boys. Boys are often favored by their parents and get more food, with the result that girls are more likely to be malnourished. Girls also get medical attention less often than boys. Infant mortality is 1.47 times higher for girls than boys.

Gender discrimination even starts before birth. Partially because of that dowry looming in the future and partially because of the financial burden associated with girls in general, Indians often try to abort girls before they are born. The practice is most common in the north, which is poorer and more traditional than the rest of India in general — but it’s also most common in the northwest, which is better-off than the Ganga Valley to the east. This is most likely because richer families have easier access to ultrasound, which lets them determine the fetus’s gender. In areas without abortion clinics or ultrasound, families can always resort to infanticide.

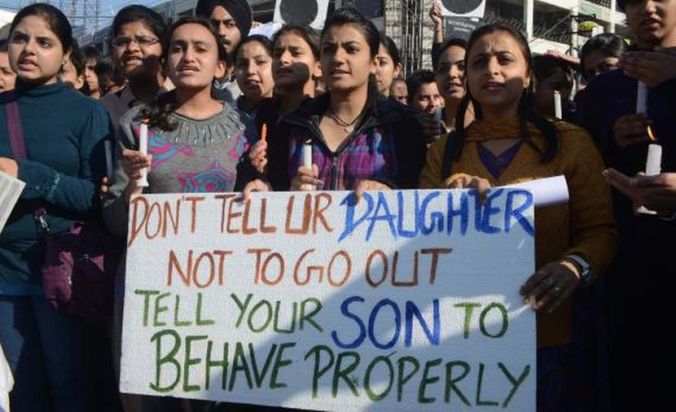

These are all long-standing problems that have vexed Indian policymakers, feminists and human rights activists for decades. But the current issue that has most galvanized these groups and attracted the most international attention is sexual violence. It’s a big problem in India, ranging from petty issues like sexual harassment on trains and on the street to massive ones like gang rape and murder. The incident that brought the issue to the fore was a gang rape in Dilli, the national capital, on a nighttime bus ride in 2012. A medical student had gone to the movies with a male friend; the assailants knocked out the friend, then raped the student with an iron rod. She did not survive. The attack touched a raw nerve and brought thousands of aggrieved women (and a few men) out into the streets to protest the lack of safety in India and a culture of impunity around rapists.

Image source: Youth Connect

Many of these problems stem from a common root: a general lack of law enforcement in India. As I pointed out before, plenty of sexist practices have been outlawed, and many of the ones I listed are illegal too: sex-selective abortion, dowry, rape, domestic violence. But they survive just the same, thanks to a combination of quiescence on the part of women and apathy and chauvinism on the part of mostly male police and courts. Indian cops rarely care if women come to them with rape stories; sometimes they laugh them off. Rapists go unpunished, which only emboldens them to strike again and again. As a result, women give up and resort to taking measures for their safety… and ultimately, spending more time in the house. Sometimes they take matters into their own hands, as when an enraged mob of women lynched a serial rapist after the court failed to punish him, but generally men get away with it. Sometimes cops even join in the rape.

There’s another tension in Indian society at work here: the massive gulf between its educated, Westernized, urban elite and its religious, minimally educated, rural masses. India may have been founded by the former and had its legal code written by them, but the latter makes up the bulk of the country. Most Indians only have a hazy idea of “Western” values and modern lifestyles, and they certainly haven’t been internalized. When these people migrate to the cities, clashes and tension result, including sexual violence. One reason the 2012 gang rape incident sparked so much outrage was because the victims were middle-class and the assailants were petty thugs, appropriate symbols for the fear and distrust separating the classes in India (as in China and elsewhere).

That being said, it’s not as if sexism is unheard of among the Indian elite as well. Remember that comparatively well-off northwest India has the most sex-selective abortion. Members of India’s far-flung diaspora, which is mostly well-educated and well-off, also look for doctors willing to tell them the sex of their fetuses and willing to abort them. Boys are more pampered and valued by their parents. It’s also not like men are the only bad guys here; Indian women can be fierce defenders of sexist attitudes as well. They have a dreadful reputation as being bitchy mothers-in-law: treating their daughters-in-law as personal servants, doting on their sons at the expense of the daughters-in-law, setting unreasonable expectations for them. There’s an entire genre of TV dramas about nasty mothers-in-law.

Finally, it must be emphasized that I am focusing on the negative aspects of gender in India. The statements I have made here are strictly generalizations. India has made huge strides in treating women fairly since independence. In most parts of the country it is now unusual not to send girls to school, and they usually do well. Plenty of families all over the country value and treasure their girls and don’t seem them as a financial burden. In cities especially, women are entering the workforce in great numbers. Call centers were a crucial factor here: they favor hiring women because they consider them better team players and less trouble in the workplace. The software industry is now 30% female. Women are breaking down more and more barriers and entering different professions; there are female CEOs and bankers. Women are prominent in Indian politics, both at the national level (Indira Gandhi ruled the country for a total of 15 years; her daughter-in-law Sonia governed from behind the scenes for a decade) and the state level (Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu all have or had female chief ministers). Local government bodies reserve a third of their seats for women. There are prominent examples of powerful women in Hindu mythology (the goddesses Durga and Kali) and Indian history (the queen of Jhansi, who rebelled against the British East India Company).

India is a vibrant and noisy (if sometimes chaotic) democracy with a very active media and public discourse. Indians have a right to protest and often exercise it. Women are becoming more outspoken about their problems and put more and more pressure on politicians and men in general to get their act together. The reaction to the Dilli gang rape was proof of that. Female celebrities, like their male counterparts, are using their fame as a platform to speak out about issues that matter to them — sexual harassment, education for girls, child marriage. In the villages, women stand up for themselves more and more, pressing for more say in how families and villages are run, more safety when going to the bathroom (“bathroom” here often meaning a field), more affordable sanitary napkins. NGOs, foreign and domestic, encourage more feminine agency under the assumption that women will be more responsible stewards of their communities. (Of course, women have always exerted leverage behind the scenes.)

But the hurdles for women in India remain daunting. Politics is still male-dominated; the prominent women in the political arena mostly relied on dynastic ties or celebrity to get where they are. Indian politicians can be bluntly sexist, blaming the victims in rape cases or dismissing the issue. India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, has spoken with outrage about rape and sexual assault, but he also abandoned his wife at a young age and gave Bangladesh’s prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, the backhanded compliment “despite being a woman… she has zero tolerance for terrorism.” Sexuality is a taboo topic in India (although it’s gradually loosening up); it’s debatable whether this has anything to do with sexism, but there are theories that sexual repression is linked with rape and sexism in general. Informal and technically illegal village councils enforce patriarchal codes and use rape as a punishment for women who break them.

The fundamental task for India is probably to address the underlying sexism and double standards in its culture. Its founding father, Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru, recognized this, but changing a culture with millennia of tradition behind it is tough. Modern attitudes toward sexuality and feminine behavior are often considered Western and therefore alien to Hindu values. India might have many female role models, but for girls in isolated villages deep in the interior, those role models might as well live in a different country. Old-fashioned virtues of purity, honor, devotion, submission, and servility predominate.

In many ways Indian attitudes towards women and gender have parallels in the Muslim world (and India has a large Muslim minority). But Hinduism, all in all, has proved more flexible toward foreign influences and changing attitudes. India’s democratic society and culture of free speech encourages its people to speak their minds and question conventions. Teeming cities like Dilli, Mumbai and Bengaluru are more open to the outside world than their counterparts in the Muslim world. South India has a decent record on female education, health, and workforce participation. All these things point to a more optimistic outlook on gender for India than, for example, its neighbor and rival Pakistan. In the meantime, the steady stream of outrageous rape headlines in India’s press continues to tarnish the country’s overseas image.

*

For a modern (and very innovative) take on the sexist messages of the Ramayana, I recommend the weird animated movie Sita Sings the Blues. Also, I should mention that Rama’s friend Lakshmana is also revered for his loyalty, and that submission and loyalty are traditionally celebrated in India regardless of gender.

I loved the painting.

LikeLike

It’s not actually a painting — it’s a still from the movie I mention in the endnote! You should check it out, it’s gorgeous.

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks for the correction, will check it out

LikeLike

Great post on Ramayana. Even I write on hindu mythology. You would like the story of how Shri Tulsidas transformed a girl into a boy.http://wp.me/p5PfBn-gz

I have followed your blog and if you like the story then do follow my blog.

LikeLike